|

Written by Dawa Ghoso, MK Ottawa Host

This was my first time reading a contemporary Tibetan story written in Tibetan. Although it does point to the lack of readily available stories of such genre, it does point to my own ignorance and lack of effort in locating such stories written in journals such as “Sbrang Char” from which this one is extracted. Thanks to Machik’s Khabda, I “discovered” Pema Tseden, the writer as I had only known him as a filmmaker. This short story touched on various themes that a Tibetan encounters on a daily basis more so for Tibetans living in a Tibetan cultural milieu. However, the main topic seems to be Tibetan religiosity as acted out on a daily mundane basis. In an unassuming way, he manages to “poke” at the longstanding and uniquely Tibetan institution of “Tulku”. Growing up in India and Nepal, I had some similar experiences as the protagonist. One of my cousin brothers was recognized as a Tulku much later in his life than usual when he was in high school. There were abrupt changes as that fact was known. Although we had the same upbringing, being born in the same remote village and coming out of Tibet at the same time leaving our families behind, this new fact changed everything. He was taken to his monastery in South India and installed as the reincarnation of a lama. Before he left, many people came to get his blessings and I was left with lot of questions such as whether I can still call him “chocho” as he was my favourite cousin brother. I learnt only after he was recognized as a Tulku that he used to visit the “Tsam-palas” (meditators) who used to live in the hills above our Upper T.C.V. schools to offer food. This short story depicts the religiosity of a young Tibetan in contemporary Tibet. It shows the negotiation of religiosity as experienced by a Tibetan youth in relation to the phenomenon of Tulkuhood. This is most starkly demonstrated by the three instances of the main character meeting Orgyan after his recognition. In the first meeting, he was forced to prostate before Orgyan against his will by his parents. At the second meeting, although he didn’t prostrate before Orgyan, he offered “khata” (offering scarfs) twice exhibiting a sense of respect towards the other person and recognizing Orgyan as a reincarnate or a being superior to him. The final meeting was a deliberate meeting where the protagonist went to see Orgyan to seek help as he was not having much luck in his life. He mentions, “…unlike before, I felt a sense of spontaneous sense of faith in him arise within me.” He also prostrated to Orgyan despite the latter’s insistence on not doing it. This eventual shift in attitude towards Orgyan as a Tulku is further cemented by his assertion that, “…I am able to call Orgyan’s separating from this world of humans as “passing into nirvana…”. Despite the eventual arising of faith for Orgyan as the tulku, the main character still shows hesitation in his religiosity as shown by this casual remark, “Following the completion of the stupa, many religious pilgrims, and even I, got accustomed to going there regularly.” The ending of the story seems to summarize the attitude of many young Tibetans towards religious practices, because although he circumambulates the memorial stupa for Orgyan out of faith and habit, he also knows that his own teeth is in there too which creates some kind of absurdity for the devotees including himself. Whether knowingly or accidently, I feel that Pema Tseden touched on a very important subject matter that is hardly discussed and examined in our society and left to be status quo out of reverence for cultural heritage. Tibetans are very proud of our Tibetan Buddhist heritage and rightly so, however, the institution of Tulku is something that many younger generations might be ambivalent about. As young Tibetans get educated in different educational systems, different philosophies, sciences, different cultural milieus etc., the concept of Tulkuhood will get harder to reconcile with what one has learnt and experienced in their current socio-cultural settings. In addition to tackling pertinent socio-cultural issues, Pema Tseden managed to put Tibetan literature among the world literatures. As a young child growing up in India and reading world literature in English, I always wished there to be a Tibetan story that can open the Tibetan world to readers around the world as the other writers did for me. Like Camus, this short story employs simple language yet saturated with potent themes. Pema Tseden is among the very few Tibetan writers published in English who has managed to open the window to Tibetan experiences to a much wider audience.

1 Comment

བོད་རྒྱལ་ལོ་༢༡༤༦། སྤྱི་ལོ་༢༠༡༩་ལོའི་ཟླ་༣་པའི་ཚེས་༢། རྒྱ་གར་ལྷོ་ཕྱོགས་རྒྱ་མཚོའི་མཐའ་ཡི་ཅན་ནེ་(Chennai)གྲོང་ཁྱེར་དུ། དགོང་མོ་དུས་ཚོད་དགུ་དང་ཕྱེད་ཀ་ཙམ་དུ་ཟླ་བའི་བསིལ་ཟེར་གྱི་འོག། གསེར་མཐའི་བརྒྱན་པའི་མ་ནི་འཁོར་ལོ་ཟུང་གི་འགྲམ་དུ་གཞོན་ཤ་དོད་པའི་བོད་ཀྱི་མཐོ་རིམ་སློབ་མ་བཅུ་གྲངས་ཤིག་འཛོམས་ཤིང་། ནང་ལོགས་སུ་བཀྲ་ཤིས་རྟགས་བརྒྱད་ཀྱི་གཡང་གིས་ཕྱུག་པའི་ཟ་ཁང་ཆུང་ཆུང་ཞིག་འདུག་སྟེ།སྒོ་བྱང་དུ་༼MOMOSaKhang༽ཞེས་དབྱིན་ཡིག་གིས་ཆེན་པོར་བྲིས་འདུག་ལ།དེའི་འོག་ཏུ་གསེར་ཡིག་གིས་བྲིས་པའི་དབུ་མེད་ཀྱིས་༼མོག་མོག་ཟ་ཁང་༽ཞེས་བཀོད་འདུག་པའི་སྟེང་དུ་གློག་འོད་ཆེམ་ཆེམ་དུ་འཕྲོ།འདི་ནི་ཐེངས་དང་པོར་༼མ་གཅིག༽་གིས་ས་ཕྱོགས་གང་སར་སྤེལ་བཞིན་པའི་ཟླ་རེའི་༼ཁ་བརྡ༽་ལ་བསུ་མ་བྱེད་སྟངས་ཤིག་ཡིན་པ་གདོན་མི་ཟ། ཐེངས་འདིར་མ་གཅིག་གི་༼ཁ་བརྡ༽་དང་པོའི་ཐོག་ཅན་ནེ་རུ་ཡོད་པའི་བོད་རིགས་མཐོ་རིམ་སློབ་མ་དང་ལས་ཞུགས་པ་བཅས་ཁྱོན་མི་གྲངས་༡༤་འཛོམས་འདུག། དེ་རུ་ས་གནས་གོ་སྒྲིག་པས་ཐོག་མར་༼མ་གཅིག༽་གི་སྐོར་མདོར་བསྡུས་ཤིག་ངོ་སྤྲོད་བྱས་ཤིང་། ལྷག་པར་དུ་མ་གཅིག་གིས་བོད་ནང་ལོགས་གཙོར་བཟུང་ནས་སྤྱི་ཚོགས་དྲ་རྒྱའི་བརྒྱུད་ལམ་ནས་སྤྱི་ཚོགས་དང་ཤེས་ཡོན་ལས་འགུལ་འདྲ་མིན་སྤེལ་བཞིན་པ། དེའི་ནང་ནས་གཅིག་ནི་དེ་རིང་གི་ཟླ་རེའི་༼ཁ་བརྡ༽་ཡིན་པ་བཅས་བཤད།དེ་ནས་བརྗོད་གཞི་གཙོ་བོ་༼བསླུ་བྲིད༽་དང་འབྲེལ་ནས་པད་མ་ཚེ་བརྟན་གྱི་སྒྲུང་ཐུང་༼ཨོ་རྒྱན་གྱི་སོ༽་བརྒྱུད་ནས་བོད་ནང་གི་དངོས་ཡོད་འཚོ་བ་གླེང་སློང་བྱས་ཤིང། དེ་ནས་བོད་ཀྱི་སྒྱུ་རྩལ་ལས་རིགས་ཀྱིས་བོད་དེ་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་སྟེང་འཁྱེར་ཡོང་བའི་ནུས་པ།གཞན་ཡང་སོ་སོའི་སེམས་ནང་དུ་བོད་ཅེས་པ་ཇི་འདྲ་ཞིག་ཡིན་མིན་སོགས་ཀྱིས་བོད་ཀྱི་སྐོར་སྐད་ཆ་བཤད་འགོ་བརྩམས། དང་པོ། ༼ཨོ་རྒྱན་གྱི་སོ༽འི་སྒྲུང་ཐུང་དེ་བཀླགས་པའི་སྐོར་ནས་བཤད་དོན།སྤྱིར་ཀློག་པ་པོ་ཁོ་རང་གིས་པད་མ་ཚེ་བརྟན་གྱི་སྒྲུང་ཐུང་༼གྲོང་ཁྱེར་གྱི་འཚོ་བ༽་སོགས་གཞན་འགའ་བཀླགས་མྱོང་བ་དང། ལྷག་པར་དུ་པད་མ་ཚེ་བརྟན་གྱི་༼ཁྱི་རྒན༽་དང་༼ཐར་ལོ༽་སོགས་གློག་བརྙན་རིགས་ལ་བལྟས་པས། ཁོང་གིས་དེ་དག་ལས་པད་མ་ཚེ་བརྟན་རང་གི་ཕ་ཡུལ་ལ་དུང་ཞེན་ཆེ་བ།ལྷག་པར་དུ་ཕ་ཡུལ་གྱི་འཚོ་བ་དང་དེའི་ཁྲོད་ནས་བོད་མི་ཚོའི་མི་ཤིགས་པའི་དད་པ།འདོོད་ཆུང་གི་འཚོ་བ།བྱམས་སེམས་ཆེ་བ།སྙིང་རྗེ་ལྡན་པ་སོགས་ནི་གླེང་རིན་ལྡན་པ།བཤད་སྙིང་ཡོད་པའི་བརྗོད་བྱ་རྐྱང་རྐྱང་ཡིན་པ་ཁོ་རང་གི་སྒྲུང་ཐུང་དང་གློག་བརྙན་ནས་གསལ་བོར་བསྟན་འདུག་ཟེར། དཔེར་ན་༼ཨོ་རྒྱན་སོ༽འི་ནང་གི་ཨོ་རྒྱན་སྤྲུལ་སྐུར་ངོས་བཟུང་བའི་སྔ་རྗེས་གཉིས་ཀྱི་ཁྱད་པར་ལས་མི་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་ཁོང་ལ་བརྩི་འཇོག་བྱེད་སྟངས་མི་འདྲ་བ། མཐའ་ན་ཁོང་གི་ཨང་རྩིས་དགེ་རྒན་དེ་ཤེས་ཡོན་ཅན་ཞིག་ཡིན་ཡང་ད་དུང་ཨང་རྩིས་མི་ཤེས་པའིི་སྤྲུལ་སྐུ་ཨོ་རྒྱན་མདུན་དུ་སྐྱབས་འཇུག་ཞུ་རུ་ཡོང་བ་མ་ཟད།མི་གཅིག་ལ་སོ་སུམ་ཅུ་ཡས་མས་ལས་མེད་ནའང་ཨོ་རྒྱན་ལ་སོ་ལྔ་བཞི་ཡོད་པར་སྣང་ནས་དེ་གཟུངས་གཞུག་ཏུ་བཞག་ནས་མཆོད་རྟེན་བཞེངས་པ་བཅས་ནས་བོད་མི་ཚོའི་དད་པའི་སྟོབས་ཤུགས་ཤིག་མངོན་ཡོད་པ་སོགས་གསུངས། གཞན་པ་གཅིག་གིས་སོ་སོའི་མྱོང་ཚོར་ལྟར་ན།པད་མ་ཚེ་བརྟན་གྱིས་བོད་ཀྱི་འཚོ་བ་དངོས་དང་འབྲེལ་ནས་བོད་མིའི་སྤྱི་ཚོགས་དེ་ད་དུང་རྗེས་ལུས་ཀྱི་རྣམ་པ་ཡིན་པ་བཤད་ཀྱི་འདུག་ཟེར། དེང་དུས་ཀྱི་འཚོ་བ་ལ་ཁ་ཐག་རིང་བའི་བོད་མིི་ཚོ་གཉིད་ལས་སད་དུ་བཅུག་ནས་བོད་ཀྱི་སྤྱི་ཚོགས་འཚོ་བ་ཡར་རྒྱས་སུ་འགྲོ་དགོས་པར་སྐུལ་མ་གཏོང་བཞིན་ཡོད་རེད་ཅེས་བཤད། ཡང་གཞན་པ་གཅིག་གིས་པད་མ་ཚེ་བརྟན་གྱིས་རང་གི་སྒྲུང་ཐུང་དང་གློག་བརྙན་བརྒྱུད་ནས་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་སྟེང་བོད་ཀྱི་འཚོ་བ་དངོས་ག་འདྲ་ཞིག་ཡིན་མིན་སྟོན་གྱི་ཡོད་པ་དང་དེ་ནི་བོད་ངོ་སྤྲོད་བྱེད་སྟངས་ཤིག་རེད་ཟེར། གཉིས་པ། འཛུལ་ཞུགས་པ་གཅིག་གིས་རང་ཉིད་རྒྱ་གར་དུ་སྐྱེས་པ་ཞིག་ཡིན་ཡང་ལྷ་སར་ཐེངས་གཅིག་འགྲོ་ཐུབ་ནས་དེར་ཟླ་བ་གཅིག་ཙམ་བསྡད་པའི་སྐབས་ཀྱི་མྱོང་ཚོར་བཤད་དོན།ཐོག་མར་ལྷ་སའི་གནམ་ཐང་དུ་འབྱོར་དུས་བོད་མི་ཞིག་ཡིན་ཕྱིན་ལོགས་སུ་དབྱེ་བ་བཀར་ནས་ཡིག་ཆ་སོགས་ལ་བརྟག་དཔྱད་དང་འདྲི་གཅོད་བྱས་ནས་དུས་ཚོད་གཉིས་མ་ཟིན་ཙམ་ཞིག་བཀག་བྱུང་བས་སེམས་ཁྲལ་དང་སྐྱོ་སྣང་ཞིག་སླེབས་བྱུང་ཟེར། ཡིན་ཡང་ལྷ་སར་སླེབས་དུས་རང་ཉིད་ཀྱིས་སེམས་ནང་བསམ་པ་ལས་ལྷག་པ་ཞིག་རེད། དེ་ལ་ཡོད་པའི་རི་མཐོ་བོ་དེ་དག་གི་མགོར་གངས་ཀྱིས་ཁེབས་ཤིང་དེའི་ཁྲོད་ན་ཕོ་བྲང་པོ་ཏཱ་ལ་གཟི་བརྗིད་ལྡན་པའི་ངང་ཡོད་པ་མཐོང་དུས་བཤད་མི་ཤེས་པའི་ཚོར་བ་ཞིག་སྤྲད་སོང་བར་བཤད། དེ་ནས་སེ་འབྲས་དགའ་གསུམ་དུ་མཇལ་སྐོར་དུ་ཕྱིན་སྐབས་ཀྱང་བོད་མི་ཚོ་ཕན་ཚུན་ལ་དགའ་སྣང་ཆེ་བ་དང་རོགས་རམ་སོགས་གནང་བྱུང་བས། བོད་པ་ཟེར་བ་དེ་ངོ་མ་བྱམས་སྙིང་རྗེ་ཆེ་བ་ཞིག་ཡིན་པ་ཚོར་སོང། ཁོང་ལ་དེ་ལས་ཀྱང་བག་ཆགས་ཟབ་པ་ནི་ལྷ་སའི་ཟ་ཁང་ནང་དུ་སོང་ན་བོད་ཇ་ཚ་པོ་ཇ་དེམ་གང་དང་པོར་སྤྲད་ཀྱི་འདུག་ལ་དེ་ནི་སྣེ་ལེན་བྱེད་སྟངས་མི་འདྲ་བ་ཞིག་མཐོང་བྱུང་ཟེར། མཐའ་ན་ལྷ་སའི་བོད་མོ་དེ་ཚོའང་སྙིང་རྗེ་མོ་ཞེ་དྲག་འདུག་ཟེར་ནས་འཛུལ་ཞུགས་པ་ཚང་མ་དགོད་སྒྲས་ཁེངས་སོང། གསུམ་པ། འཛུལ་ཞུགས་པ་གཞན་འགས་བོད་དེ་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་སྟེང་མཉམ་དུ་འགྲོ་ཐུབ་པར་ཚོང་ལས་དཔལ་འབྱོར་གྱི་ཐད་ནས་ནུས་ཤུགས་འདོན་དགོས་ཚུལ་དང་། དེའང་གཅིག་གིས་ཁོ་རང་རྒྱ་གར་དུ་དགུན་ཚོང་བྱེད་དུ་འགྲོ་མྱོང་ཡོད་ལ་དེ་རུ་བོད་མི་ཚོང་བ་ཚོས་རྡོག་རྩ་གཅིག་སྒྲིལ་ངང་ཚོང་ལས་གཉེར་སྟངས་དེས་སེམས་ཤུགས་འཕར་མ་ཞིག་གནང་སོང་ཟེར།དེར་ཡོད་ཚོང་བ་ཚང་མས་རྒྱ་ནག་གི་ཅ་དངོས་གཅིག་ཀྱང་མི་བཙོང་བར་བོད་མི་རང་ངོས་ནས་བཟོས་པའི་ཅ་ལག་བཙོང་གི་འདུག། གལ་ཏེ་བོད་མིས་བཟོས་པའི་ཅ་དངོས་འདི་དག་ཚོང་རྭ་ཆེན་པོ་དེ་འདྲ་རུ་འགྲོ་ཐུབ་ན་ཁོང་ཚོའི་ཚོང་ལས་དཔལ་འབྱོར་ཡར་རྒྱས་དང་བོད་མི་ཚོང་གཉེར་བ་དང་ཁེ་ལས་པ་མང་པོ་ཐོན་ཐུབ་རྒྱུ་རེད་གསུངས།

བཞི་པ། འཛུལ་ཞུགས་པ་གཅིག་གིས་རང་ཉིད་གློག་ཀླད་དང་འཕྲུལ་ཆས་ཚན་རིག་ཐོག་སློབ་གཉེར་བྱེད་པའི་བརྒྱུད་རིམ་ཁྲོད་ནས་བོད་ཀྱི་དེང་དུས་འཕྲུལ་རིག་གི་སྐོར་ལ། ཐོག་མར་བོད་ཀྱི་སྐད་ཡིག་དང་རིག་གཞུང་སོགས་གལ་ཆེན་པོ་ཡིན་པ་དང་དེ་དག་སྲུང་སྐྱོབ་བྱེད་རྒྱུ་ནི་དེ་ལས་ཀྱང་གཙིགས་ཆེན་རེད། ཡིན་ཡང་དེ་ཚོ་དུས་རབས་དང་མཐུན་པར་འགྲོ་མ་ཐུབ་ན་ནམ་ཞིག་ཉམས་རྒུད་དུ་འགྲོ་རྒྱུ་ཡིན་པ་ཉག་གཅིག་རེད་ཟེར། བོད་ཕྱི་ནང་གང་ཡིན་ཡང་ད་ལྟའི་ཆར་དེང་དུས་འཕྲུལ་རིག་ཤེས་བྱའི་སྐོར་ནས་ད་དུང་རྗེས་ལུས་ཡིན་པ་དང་། འདིའི་སྐོར་ནས་བོད་མི་གཞོན་སྐྱེས་མང་པོ་སྐྱེད་སྲིང་བྱ་རྒྱུ་གནད་འགག་ཡིན་པར་གསུངས།གལ་ཏེ་དེང་དུས་ཀྱི་འཕྲུལ་ཆས་དང་དྲ་རྒྱའི་དུས་རབས་འདིར་བོད་ཀྱི་སྐད་ཡིག་བེད་སྤྱོད་ཀྱིས་སྤྱོད་སྒོ་ཆེ་རུ་སོང་ན་སྐད་ཡིག་སྲུང་སྐྱོབ་བྱེད་སྟངས་ཤིག་ཡིན་པ། དྲ་རྒྱའི་བརྒྱུད་ལམ་ཁག་ནས་གཞོན་སྐྱེས་ཚོས་བོད་ཡིག་དང་སྐད་ཡིག་གཞན་མཉམ་དུ་བེད་སྤྱོད་བྱེད་དགོས་པ་གལ་ཆེན་པོ་ཡིན་ཚུལ་སོགས་ཚོར་ཤུགས་ཆེན་པོས་བརྗོད་སོང་། ལྔ་པ། འཛུལ་ཞུགས་པ་གཅིག་གིས་ཁ་བརྡ་འདི་བརྒྱུད་ནས་ང་ཚོ་ཚང་མས་ཕ་ཡུལ་བོད་ལ་རྒྱུས་ལོན་མང་དུ་བྱེད་དགོས་པ། བོད་ཕྱི་ནང་གཉིས་ཀྱི་གནས་སྟངས་དང་བོད་མིའི་འཚོ་བ།གཞོན་སྐྱེས་ཚོས་བོད་ཀྱི་རྩ་དོན་ཐད་ནུས་པ་མཉམ་སྤུངས་དགོས་པ། དེ་ཡང་ཡིན་གཅིག་ཆབ་སྲིད་གཅིག་པུ་ཡིན་པའི་ངེས་པ་མེད་པར།༼མ་གཅིག༽་ནང་བཞིན་བོད་ཕྱི་ནང་གང་ཡིན་རུང་ལས་དོན་འདྲ་མིན་ཐོག་ནུས་པ་འདོན་རྒྱུ་འདུག་ཏེ། ཤེས་ཡོན་ཡར་རྒྱས། སྤྱི་ཚོགས་ཡར་རྒྱས། དཔལ་འབྱོར་ཡར་རྒྱས། རིག་གཞུང་རྒྱུན་འཛིན། སྐད་ཡིག་སྲུང་སྐྱོབ་སོགས་རང་རང་སོ་སོས་ནུས་པ་གང་ལྕོགས་ཀྱིས་འགན་འཁུར་ལེན་རྒྱུ་བྱུང་ན། བོད་ནང་དང་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་ཐོག་ཏུ་བོད་ཀྱི་ངོ་བོ་འཛིན་ཐུབ་པ་དང་བོད་མི་རིགས་ཀྱི་ཆིག་སྒྲིལ་ལའང་ཕན་ཐོགས་ཆེན་པོ་ཡོད་ཚུལ་བརྗོད། དྲུག་པ། འཛུལ་ཞུགས་པ་རེ་འགས་བོད་ཀྱི་གླུ་གཞས་སྒྱུ་རྩལ་གྱི་སྐོར་ནས་བཤད་དོན།ཁོ་མོ་ནི་རྒྱ་གར་དུ་སྐྱེས་པ་ཞིག་ཡིན་མོད་བོད་ནང་གི་གླུ་གཞས་ལ་ཤིན་ཏུ་དགའ་ཞིང་གཞས་མ་ཚེ་དབང་ལྷ་མོའི་གླུ་སྐད་ཀྱིས་ཕ་ཡུལ་བོད་དང་སེམས་ཐག་ཉེ་རུ་ཡོང་བའི་ཚོར་སྣང་སླེབས་ཀྱི་འདུག་ཟེར། དེར་བརྟེན་ནས་བོད་ནང་ལོག་གི་བོད་མི་རྣམས་མི་རིགས་ཀྱི་ལ་རྒྱ་ཆེ་བ་དང་མི་རིགས་ཀྱི་འདུ་ཤེས་ཟབ་པ་ཤེས་པས། རང་ཉིད་ཡིན་ཡང་ནམ་རྒྱུན་བོད་སྐད་གཙང་མ་བཤད་ཅི་ཐུབ་དང་བོད་གཞས་ལ་ཉན་གྱི་ཡོད་ལ་དེ་འདྲ་བྱེད་ཐུབ་ན་ཡག་པོ་མཐོང་སོང། ལྷག་པར་དུ་ནུབ་ཕྱོགས་སུ་ཡོད་པའི་བོད་མི་ན་ཆུང་དང་གཞོན་སྐྱེས་ཚོས་འདིའི་ཕྱོགས་ནས་དོ་སྣང་བྱེད་ཐུབ་ན། བོད་ཀྱི་གླུ་གཞས་སྒྱུ་རྩལ་ཁྲོད་ནས་ང་ཚོ་ཚང་མ་བོད་པ་གཅིག་ཡིན་པའི་འདུ་ཤེས་བསྐྲུན་ཐུབ་པར་ཕན་ནུས་ལྡན་པར་གསུངས། མཐའ་མཇུག་ཏུ། ས་གནས་གོ་སྒྲིག་པས་ཁ་བརྡ་བ་ཚང་མར་མཉམ་འཛོམས་བྱུང་བར་བཀའ་དྲིན་ཆེ་ཞུ་བ་དང་སྦྲགས་རང་ཉིད་ཆུང་དུས་སུ་བོད་དུ་སློབ་གྲྭར་སོང་མྱོང་ཡང་བོད་ཀྱི་གནས་སྟངས་དང་༧རྒྱལ་བ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་སྐོར་སོགས་ཅི་ཡང་ཤེས་ཀྱི་མེད་པ་དེར་ཕྱིར་འདང་ཞིག་རྒྱག་བཞིན། རྒྱ་ནག་གིས་བོད་དུ་བཟུང་བའི་སྐད་ཡིག་རྩ་མེད་བཟོ་བའི་སྲིད་ཇུས་ལག་བསྟར་བྱས་པ་དེ་སྔོན་མ་ནས་ཡོད་པ་གཞི་ནས་ཚོར་བ་དང་། བོད་ནང་གི་སློབ་གྲྭ་ཁག་ཏུ་༠༨་ལོའི་ཞི་རྒོལ་ཆེན་མོའི་རྗེས་སུ་སྲིད་ཇུས་ངན་པ་དེ་ཤུགས་ཆེན་སྤེལ་བར་བལྟས་ན།ད་ལྟ་ཕྱི་ལོགས་སུ་ཡོད་པའི་ང་ཚོ་བོད་པའི་གཞོན་སྐྱེས་ཚོས་བོད་ཀྱི་སྐད་ཡིག་མི་ཉམས་རྒྱུན་འཛིན་བྱེད་དགོས་པ། དེའང་ཉིན་རེའི་དྲ་ཐོག་གི་འཚོ་བའི་ནང་པར་གཅིག་བཞག་རུང་འོག་ཏུ་བོད་ཡིག་གི་མཆན་འབྲི་བ་ནས་འགོ་བཙུགས་ནས་ཉིན་རེའི་ཟིན་བྲིས་ཐན་ཐུན་བོད་ཡིག་ནང་འབྲི་བ་སོགས་ནས་བོད་ཡིག་བེད་སྤྱོད་བྱེད་ན་འགྲིག་ལ། དེ་ལས་ཀྱང་བཟང་ན་བོད་ཀྱི་སྐད་ཡིག་ཡར་རྒྱས་དར་སྤེལ་གཏོང་ཐུབ་རྒྱུ་དེ་རེད། བོད་ཀྱི་སྐད་ཡིག་དང་རིག་གཞུང་ལ་སློབ་གཉེར་བྱས་ནས་དེང་དུས་ཀྱི་སྤྱི་ཚོགས་དང་མཐུན་པའི་ངང་བོད་ཀྱི་ཐ་སྙད་གསར་པ་བཟོ་བ་ནས་བོད་ཀྱི་རྩོམ་རིག་སོགས་ནུབ་ཕྱོགས་སྤྱི་ཚོགས་སུ་ངོ་སྤྲོད་བྱེད་པ་སོགས་ལས་དོན་འདྲ་མིན་བརྒྱུད་ནས་བོད་ཀྱི་རིག་གནས་སྲུང་སྐྱོབ་བྱེད་རྒྱུ་དེ་གལ་ཆེན་ནང་གི་དོན་ཆེན་ཞིག་ཡིན་པ་བཤད་ནས་ཁ་བརྡ་ཐེངས་དང་པོ་ལེགས་འགྲུབ་ངང་མཇུག་བསྡུས་སོ། ས་གནས་གོ་སྒྲིག་པ། ཀུན་ཚེ་ནས་སྤེལ་བ་དགེའོ Written by MK Kathmandu Host The venue of our gathering was at SIT Study Abroad Nepal: Tibetan and Himalayan people, which surprised most of us since it was a lovely location still in touch with nature and old Himalayan architecture styles, smack in the middle of bustling Boudha in Kathmandu. Our Khabda started with conversations and introductions, which was followed by a brief overlook on Pekar’s works and the reading that described her journey so far. While in the process of the brief introduction on her struggles of fitting in the society in Dharamshala after coming from Tibet, we were all able to relate on some level of the inclusions and exclusions that take place within the Tibetan society in exile. This opened a really long and complicated discussion on Tibetan identity. An important point made that was highlighted in the discussion was the derogatory name that is used even today in exile societies to call Tibetans coming from Tibet. Used with the intention of making them feel unwelcomed, and different. Not realizing that when one leaves Tibet due to desperate measures, in search for a better life, hope and a new home. They are very vulnerable. Many leave families behind, and journey alone with no one to rely on and no one to console them in a country they have never set foot on until now. Although maybe there are good facilities and systems now to help them re-settle, a lot of times in such programs we do not discuss about their mental health. In the case of Pekar’s story, we can see how society can make a person who is confident come to a breaking point, the conversation on mental health, depression and such related topics even today are hardly talked about in the society. It was sad to see the society hound Pekar and call her a ‘madwoman’ instead of supporting her and encouraging her in her fragile state of mind. There are so many things we need to improve on, I know there is no perfect society but there needs to be progress in the right direction. We as a society need to discuss such issues, learn from them and evolve our mindsets, to see how we can practice more of the compassion we always talk about in our day to day lives. The heavy discussion on the inclusion and exclusion in terms on Tibetan Identity, we talked more in depth about being comfortable with being Tibetan, as much as Nepali, or Indian, or American or German, etc... Not criticizing each other but accepting and respecting every individual's journey, and giving them a supportive environment or space to explore it. One interesting personal experience someone shared with us was about how difficult it is to travel with an RC or the Tibetan Refugee identity, the person is young but with the identification he had, travelling was hard and many times personally very uncomfortable in terms of how he was received or treated by officials at checkpoints. He recently got a Nepali passport, and he described this feeling of being empowered, to be able to go anywhere, to be able to ride a plane, to be able to just travel. This did not change how he felt, he did not become less of a Tibetan. The idea being that we decide who we are and take the steps to empowering ourselves. Then came a really interesting discussion on how many cultures in Nepal, identify themselves as Nepali but speak Tibetan. We had a lovely person share her experience openly about her mixed heritage, she being Gurung and Tibetan. Feeling very comfortable in both, but many a times there is quite a big population that maybe speaking in Tibetan, but feel Nepali, like the Mustangs, Gurungs, Dolpo, etc… and why so. This maybe an interesting discussion in the future to have as well. But, in many ways even within the people who very much identify themselves as Tibetan we do need to acknowledge that we too have our comfort zones. Like Tibetans who went to TCV, or who went abroad, Europe or USA, or Nepal, within that being U-tsang, or Kham or Amdo and speaking in that dialect or a regional dialect. All of it, we do have these different experiences but what unites us is being Tibetan, feeling Tibetan, identifying as one. But we do not give that space or are exclusive many times about the space we give when we are a certain kind of majority to the minority. Something to think about in general. In the end, we went back to Pekar’s experience and words from Fading Dreams that really stood out to many of us:

How beautifully expressed are the words of Pekar, it was brought up how Buddhism played an important role in her experience to becoming who she is. The idea of practicing Buddhism in order to find peace and liberation is something to rethink and look more deeply into. Every journey is different, but in Pekar’s maybe practising buddhism and compassion in a society that traumatized her resulted possibly in her breaking down. Practicing Buddhism has brought many to the point of breaking down, it isn't all peace but an inner battle. How do you practice compassion in an environment so negative. While doing so, we many a times neglect being compassionate to ourselves, we don't take care of ourselves. Maybe that was her journey to her liberation. Being compassionate, is deeper than we think and many times it breaks us apart, so we can rebuild ourselves. Just like a white lotus that grows out of the muddy water. Today Pekar, is an inspiration to so many women out there, We personally draw so much strength from her work. We find parts of ourselves scattered in her artwork, in the story she tells and it gives us courage to be true to ourselves. It is time women are appreciated for their work and their contribution to society, for women to explore their potential, for women to be equal to their male counterparts and for women to have safe spaces within the Tibetan society.

Also, at the end we must acknowledge and respect the people who supported her and helped give her the environment to build herself up. We need more spaces like Amnye Machen Institute and people like Gyen Tashi Tsering, Jamyang Norbu, Lhasang Tsering and Pema Bhum. They provided a safe space to many and are a great role model on what kind of spaces we need to create and the mindset we need to incorporate in our society today. Two weeks ago, we had our second Machik Khabda program take place in 22 different locations around the globe. We welcomed ten new local hosts into this program from places such as Calgary, Minneapolis, Helsinki, Dharamsala, and Bengaluru. The usual protocol for Khabda is that once a gathering takes place, we ask local hosts to share with us some updates on how their conversations went. Quite often, people write brief notes and we're thankful for that as it takes extra time and energy to organize, host, and then share feedback about Khabda. However, when people do share longer reflections, we're extremely grateful for that as this allows us to better understand the evolving mechanics of Khabda and see what we can do to improve and elevate this experience for those interested in organizing and joining along. Below, we have selected four quotes that speak on the general atmosphere of the following Khabda gatherings and what discussion points got highlighted during their respective chats. We hope these words offer a glimpse into the ground reality of Khabda - an experience facilitated by Machik but in the end, shaped by people like yourselves. To write for the Khbada Blog, do get in touch with us at [email protected]. by Lekey Leidecker

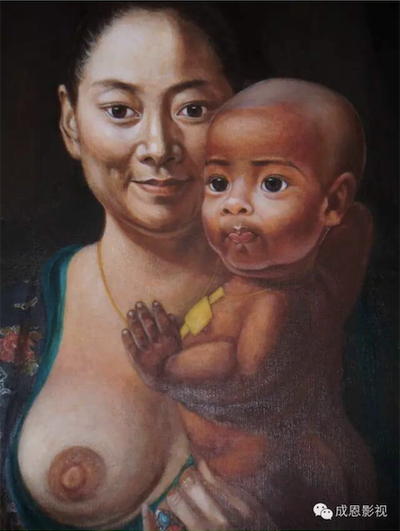

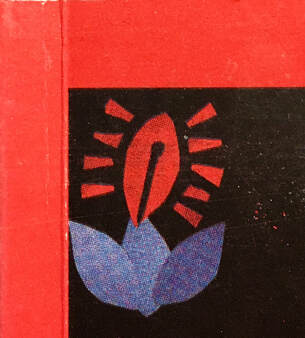

I first saw myself reflected in an art exhibit at age twenty. I dragged my family down the 7 train line for Anonymous: Contemporary Tibetan Art at the Queens Museum in New York City. The first all-women Tibetan artists exhibition, titled མ། (En: Her) opened on September 24, 2017 at Scorching Sun Art Lab in Lhasa. I am embarrassed to admit that my first reaction (after delight) was surprise that enough female Tibetan artists existed to create an entire exhibition. I share this story to illustrate that, like many Tibetans of my generation and circumstances, our interactions with Tibetan creativity are often so limited that we don’t believe it exists. Nothing could be further from the truth, which Machik Khabda aims to highlight and celebrate! Imagine, then, my surprise and excitement to learn about a Tibetan woman artist who has been boldly creating works of self-expression for over twenty years: Monsal Pekar Desal. Born in Atro, Gaba (near Jyekundo) in Kham, she has been a constant vocal advocate for Tibetan women, a prolific creative, and vastly underrecognized. Pekar Retrospective We were thrilled to see how the inaugural Khabda generated excitement and energy to engage with and celebrate the works of some our community’s most brilliant contemporary creative minds. In the lead-up to the April 20, 2019 Khabda, my social media flooded with the compelling works and words of this Tibetan woman creative, and so many communities engaged with the immense talent, conviction, and energy of Pekar. We on the Machik team look forward to hearing more of your reflections from each of the 22 Khabdas that took place over the course of the day, all over the world! In DC, two main intertwining threads emerged from our discussion: identity and creativity, particularly Tibetan. Our lively conversation over samosas ranged from a discussion of aesthetics and self-expression to personal anecdotes of interactions with Pekar. Dr. Losang Rabgey la, Machik’s Executive Director and Co-founder greeted and thanked participants for joining the discussion and explained the impetus for choosing to highlight Pekar’s work: she has persisted pursuing her creativity despite incredible odds, and her work has not yet gotten its due recognition. Prominent Tibetan-language writer Tsering Kyi la, who provided the initial spark to focus this month’s Khabda on Pekar, shared her thoughts on Pekar’s work and significance in today’s world. The two women met when Tsering Kyi first arrived in India from Tibet. In our Khabda, Tsering Kyi shared how Pekar’s support helped ease her transition into a new society and culture, a transition that Pekar herself went through. Tsering Kyi explained that Pekar’s work and life asks us all to embrace women’s bodies while removing the stigma and objectification with which we typically regard them. This point led to a fascinating discussion of the ways that nudity was or was not taboo in traditional Tibetan society and in art, and how the influence of India and Christianity in exile and of dominant Chinese culture inside Tibet are changing this. As accomplished Tibetan artist Losang Gyatso la (browse his excellent Facebook page New Tibet Art here) highlighted at our DC gathering, Pekar is even more astonishing in her uniqueness because of her background. Her path to art as a form of creative self-expression was anything but straightforward: her region in Tibet is relatively far from the typically considered “centers” of Tibetan cultural production such as Lhasa and parts of Amdo (i.e. Rebgong, a well-known hub of writers and artists). Additionally, while her father was an accomplished thangka painter and sculptor, during the repressive years of the Cultural Revolution he hid his talents even from his own daughter. Her own artistic training in a Socialist-Realist style at Northwest Minorities University in Lanzhou would have contrasted greatly with the traditional Tibetan aesthetics which likely flourished in her home community. With her background in mind, Gyatso la reflected that Pekar’s art has often conveyed a sense of struggle, of being caught between worlds and identities, but has lately taken on a new sense of freedom and joyfulness, as reflected in the series of paintings featuring Tibetan women that she completed in 2018. The accompanying piece of writing, originally in Chinese, translated for Khabda by Jin Ding, is an urgent call for women to embrace themselves fully and to “rise” from the countless obstacles we face --from patriarchal violence to the pain and challenge of motherhood-- to “with our own sisterhood and wisdom, kindle light for other women.” Dr. Losang Rabgey la pointed out that her drive for social change and gender equity, often expressed through her art, derives from her own life experiences and highlighted a section in her 2004 book Women's Status in Tibetan Society: Don't Laugh at Women's Hardships where Pekar describes the pain of witnessing the abuse that one of her close friends experienced after her marriage. “All art is essentially self-portraits” Tibetans in and outside Tibet face many challenges and rapidly shifting contexts, and contemporary Tibetan artists gift us with their negotiations of a complex world and helps our society to self-reflect and to grow. Gyatso la’s insights into Pekar’s creative and stylistic development from an artist’s perspective affirmed what I already felt: her work reflects her own challenges and struggles faced as a Tibetan, a woman, and a creative individual, and that is part of what makes her work so valuable. Some may ask why it even matters to feel reflected in contemporary media at all, and many have explored this answer much more astutely than I can. What I can say is that encountering Pekar’s art has affirmed my impulse not just to create, but to create on my own terms. Like all good art, Pekar’s work may challenge or surprise us, but shows us something about ourselves. For a Tibetan woman like me, the value of that is immeasurable. Shining Vaginas and Feminine Power As we continue to build Bhoepa spaces that actively include people who are not reflected in a male-female binary, I think that Pekar’s call for unapologetic Bhoepa authenticity and her celebration of femininity can bolster us for that necessary and exciting work, providing a burst of energy for the ongoing gender equity work in Tibetan communities. We were thrilled to have Drokmo, a Dharamsala-based NGO working for gender equity in Tibetan communities, convene a Khabda in Dharamsala, and so delighted that Pekar’s daughter, currently a student at Tibetan Children’s Village, could attend and share her own insights into her mother’s life and work! Get Creative We closed our Khabda with a wonderful painting session led by painter (and former Machik Intern!) Sam McKeever, who led the group on a session focused on color as therapy and the freeing properties of self-expression. There is so much that remains to be explored about her vast body of work, and we are fortunate that she is still active inside Tibet today. As Dr. Tashi Rabgey la highlighted in our discussion, not so much as an essay has been published about Pekar’s work in the last fifteen years! Her work, given due attention and consideration, will influence and shape future generations of Tibetan creatives. In the meantime, I’m waiting for whatever budding Bhoepa filmmaker will make the first feature film about Pekar’s life! Lekey Leidecker Machik |