|

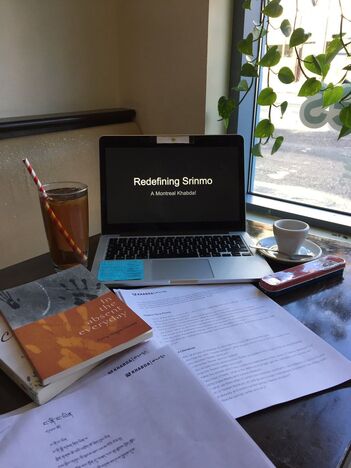

Written by Tenzin Rabga, MK Chicago

First and foremost, as two male members of the community we acknowledged from the beginning that we have to be both mindful and incredibly humble in our understanding (or lack thereof) of women’s issues in our community. We feel that since we have not and will not live their experiences, we can but only speculate and not speak of what it is really like to be a woman in the Tibetan context. Nevertheless, we noticed that the notion of srinmo - a barbaric, untamed, uncivilized creature, is laden with patriarchal biases that cast the female inferior to the male, and as a negative existence. It was also brought to our knowledge that the whole srinmo imagery might also have deeper cultural and religious roots, particularly relating to the depiction of the traditional Bon culture as the barbaric and untamed and the imported Buddhist values as civilizing and taming the beast. However, this does not eradicate the pervasive gender-based implicit and explicit biases in this imagery. Dhondup made a poignant point, that any “redefining” of our history is determined by the demands of the present. Therefore, what gen Palmo does with her redefining the srinmo is a reflection of our current times, where women have taken ownership of their own narratives and how they are portrayed. We also noted that there appears to be a significant gulf between the literate authors and their circles, and the illiterate peasants and villagers who live these experiences. It was brought to our attention that the general readership in Tibetan has been declining overall. We realize that this is an issue that prevents authors such as gen Palmo from fully reaching to her audiences. We wondered if other avenues and forms of mass media could be used to bridge this gulf. Radio broadcasting appears to be more accessible to the general population. We then discussed ways in which our communities could help create a safer and more conducive environment for healthy and helpful discussions on gender inequalities. We noticed that particularly in our Tibetan communities, the powerful and influential figures have a role to play in this regard. Their encouragements and directions can help ease the conversations and bring about meaningful changes, for example the establishment of the geshema degree for nuns. We also realize that change has to come from a groundswell of popular movement. For this, education is foundational. We come away from this discussion with a somber dismay at the state of affairs of Tibetan literary culture with the declining readerships, but with a renewed sense of urgency that we need to read more Tibetan, and learn about more female Tibetan authors in particular.

1 Comment

desire within Tibetan women come to be entangled as they come into the world (family expectations and male hunger) all while maintaining space for the contradictions innate to the experience of womanhood. Indeed, Gen Palmo asserts that she is many things at once: she is immaculate, pearl, contract, commodity, country and wisdom. What struck our group the most was the ways in which she played with metaphors and images with great skill. In Approach Me Not Gen Palmo rejects classical images of Tibetan women (often likened to pearls and nectar in songs and poems) in favour of gruesome ones (charcoal and poison streams). In doing so, she effectively dismantles the image of the resplendent, static woman whose body is property, instead imbuing the figure of the woman with complexity, with dangerous potentiality.

Overall, this Khabda helped us challenge both our understandings of Tibetan womanhood and Tibetan literature. One participant, a male McGill PhD student remarked on how his understanding of Tibetan poetry had shifted entirely, having now reconsidered the role of gender within dominant modes of learning and writing. More broadly, we discussed how women shaped Tibetan landscapes in the context of communities both inside and outside Tibet. In line with this, we discussed my personal favourite stanza of Gen Palmo’s poem I am who I am: “I am who I am / I am a queen / A mother, whose golden vessel of a womb gave birth to the children of a nation / Averting the fall of Tibet’s ancient traditions in calamitous times / I hoist and raise the pillar of earnestness / When my life is vested with power and equality / I am country.” Tibetan women, in a sense, are carriers of place. Carrying lakes, mountains, stones, Tibetan women form a vast country in a time of seeming placelessness. However, this worlding remains conditional on both power and equality as Gen Palmo reminds us. Redefining srinmo, as such, must entail a collective project of examining and dismantling gender roles, a realization that the spirit of srinmo is wild, powerful and endlessly creative. As the first Khabda Week of 2020 rolls out, we want to thank all our local hosts for joining us in celebrating the visionary spirit of Professor Huamo Tso and her remarkable work for Tibetan women.

Each Khabda carries a unique spirit as they reflect an array of local hosts and communities. The Machik team curates the Khabda topics and then an amazing community of global participants take part. Given the current global spread of the coronavirus (covid-19), we are closely monitoring recommendations of health officials. Since Khabda takes place in many different communities around the world, we strongly encourage all local Khabda hosts and participants to follow preventive measures recommended by your local health authorities (such as the CDC in the USA) and the advice of groups such as the WHO. The safety of all participants is a top priority. Here are some key tips:

We sincerely thank everyone taking part in Khabda this week as part of our celebration of International Women’s Day and we look forward to hearing from your local gatherings! For any questions or concerns, please write to us at info@machik.org Machik Team |